At 77 years old, Carl McLain appears to be the picture of health. His half smile and twinkling eyes hint at a mischievous sense of humor.

But eight years ago, he was far from feeling healthy. Mysterious symptoms such as pain in his legs, depression, anxiety and trouble sleeping led him to see one specialist after another in New Mexico, where he was living at the time. The diagnosis was mixed.

“I thought the pain in my legs was because of exercise, so I exercised harder,” he said.

He moved to San Antonio at the invitation of his daughter, Dina McLain Tom, MD, an associate professor of inpatient pediatrics at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Within a week, he met with a neurologist, was tested and diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

“Looking back now, all the classic Parkinson’s symptoms I read on the internet were a description of what I had,” he said.

For seven years, he managed his symptoms with medication. However, the medication prescribed caused other symptoms, such as dyskinesias, involuntary movement in the arms, legs, face and trunk.

When the medication began to diminish before the next dosage and his symptoms worsened, McLain was given a surgical option to alleviate some of his symptoms — deep brain stimulation. Initially, he was reluctant until his neurologist, Sarah Horn, MD, at UT Health San Antonio, explained the window of time he had to decide.

“I thought brain surgery might not be a good idea,” he said. “But then I realized if I waited too long, I might not be able to get it done, and that scared me more.”

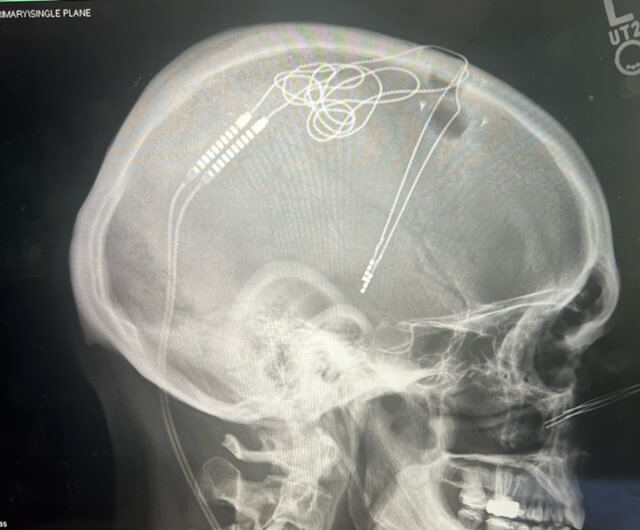

Deep brain stimulation is the placement of electrodes in the brain connected to a battery-operated generator in the chest similar to a cardiac pacemaker. A small impulse of electricity moves from the generator to the electrodes to stimulate a specific area of the brain, relieving some symptoms and side effects.

“Typically, an electrode is placed on each side of the brain,” said Alexander Papanastassiou, MD, a UT Health San Antonio neurosurgeon

who performed the surgery on McLain. “The generator is like a pacemaker for the brain.”

The surgery was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1997 as a treatment for Parkinson’s, according to the Parkinson’s Foundation. After the surgery, Parkinson’s patients typically can enjoy ongoing freedom from Parkinson’s medicines wearing off before the next dose and extra movements caused by the medicines, but it is not a cure, Papanastassiou said.

“DBS helps smooth out the treatment effects of medicine, and the medicine and electricity work together so the symptom control stays constant during the day. It doesn’t wax and wane over the day,” he said.

Patients such as McLain continue to have Parkinson’s symptoms, such as constipation, fatigue and insomnia.

“The thing that amazed me is how much of my symptoms are cognitive,” McLain said. “I got rid of the tremors but could see other parts of the disease were continuing.”

By improving relief from motor symptoms, the treatment does give patients a better quality of life, Papanastassiou said.

“Imagine you’re awake for 16 hours a day, but for four of those hours, you have severe Parkinson’s symptoms,” Papanastassiou said. “DBS gives people their life back.”

Not all patients are eligible for the surgery. Patients are evaluated to ensure they can undergo DBS. Dementia and untreated, active depression are the two conditions that can make a patient ineligible.

“Insertion of the electrodes can make dementia worse, so we always test people’s neuropsychological function to ensure they don’t have dementia,” Papanastassiou said. “If someone has active depression, DBS can make it worse. But if someone has depression that is well treated, then it’s safe to proceed.”

Today, McLain is grateful he was eligible for the surgery. When he removes a cap, the surgical scar and electrodes are almost imperceptible to a casual observer. McLain said the number of his daily pills had been cut in half. Tremors and episodes of dyskinesias are all but gone. McLain has taken up playing the guitar again and enjoys jam sessions with his grandchildren.

“It’s been a turning point in my life,” he said. “It’s as close to a miracle as I’ve experienced and is a blessing.”

With an eye to a future without Parkinson’s, McLain has chosen to donate his brain to the brain bank at the Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer’s and Neurodegenerative Diseases at UT Health San Antonio.

To learn more about DBS and hear experts such as Papanastassiou talk about the treatment, attend the Deep Brain Stimulation Therapy for Parkinson’s Disease: Is it Right for me? seminar on July 8 at 10 a.m. at UT Health San Antonio. RSVP here.