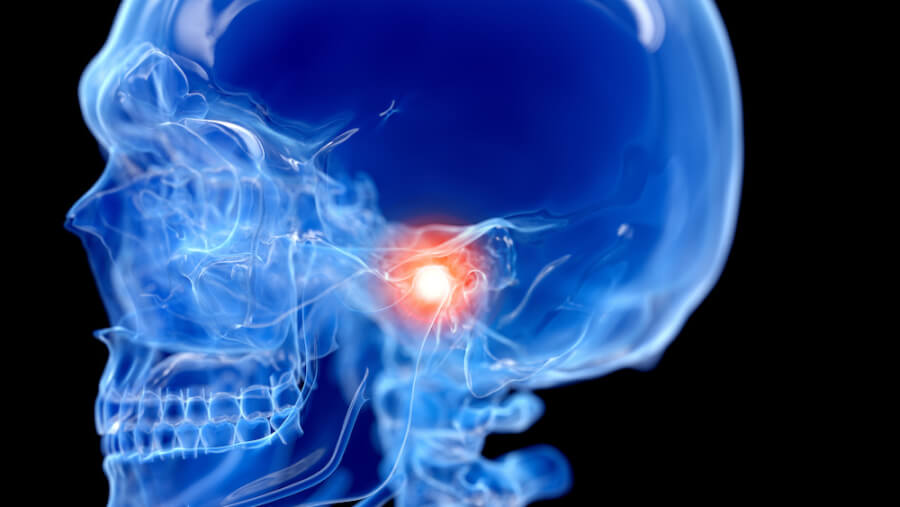

Chronic pain is one of the most common health conditions worldwide. Back pain is the most frequently reported type, followed closely by head and face pain linked to temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorder.

While not life-threatening like cancer or infectious disease, chronic pain can dramatically diminish quality of life and functional lifespan. As mobility declines, people may face limited career options and increasing difficulty performing basic daily activities. Epidemiological studies suggest that chronic pain may shorten lifespan by as much as 10 years due to reduced physical activity and overall health decline.

“Facial joint and muscle pain can interfere with eating and speaking. Chronic pain can be devastating over time,” said Armen N. Akopian, PhD, professor in the Department of Endodontics at the School of Dentistry, who is leading the charge for the project arm located at The University of Texas at San Antonio (UT San Antonio).

A renewed investment in TMJ pain research

A five-year, $9 million National Institutes of Health National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke study that began in 2022 recently received approval at the three-year mark, allowing investigators to continue their work examining the biological mechanisms of TMJ disorders. The UT San Antonio project is part of a national consortium of five institutions conducting complementary studies across the country. The ultimate goal is to create a launchpad for the development of the first targeted, non-opioid treatment for chronic pain associated with muscle and joint dysfunction.

NIH’s continued investment provides an opportunity for UT San Antonio to expand both its scientific impact and institutional visibility in pain research.

“For UT San Antonio, this grant elevates our national visibility and validates the Center for Pain Therapeutics and Addiction Research we have built,” Akopian said. “If we use this opportunity well, it can lead to breakthroughs that reshape the field and firmly establish our institution as a leader in pain research.”

Mapping the biology of facial pain

During this phase of the project, the UT San Antonio team aims to identify and characterize trigeminal neurons that innervate facial muscle and TMJ tissues, cataloging differences across male, female and older mice with and without TMJ disorder. Researchers will also create detailed maps of afferent neurites — projections from a neuron’s cell body — that innervate facial muscle and TMJ tissue, defining their location, plasticity and phenotype in mice and non-human primates. These maps will help scientists understand where and how pain originates and how it travels to other parts of the body.

The work extends to human studies as well, with the team examining and cataloging nerve and cellular plasticity in tissues from patients with myalgia and TMJ disorders.

At the core of this effort is a focus on neuronal excitability. Pain begins when sensory neurons become sensitized and hyperexcitable — a process shaped by interactions between neurons and non-neuronal cells in muscles and joints.

“Although pain is ultimately processed in the brain, it must first be generated by sensory neurons,” Akopian said. “Just as vision requires eyes to initiate visual processing, pain requires functioning sensory neurons. Without understanding what happens at this initial and focal point, we cannot design effective treatments.”

From sensitization to chronic pain

After sensitization, stimuli that were once harmless may become painful, a phenomenon known as allodynia. Painful stimuli may also become disproportionately severe, a condition called hyperalgesia.

Akopian’s team examines pain at multiple levels — including patient-reported experience, neuronal firing patterns, gene expression changes that control excitability, and signaling from non-neuronal cells in affected tissue. Together, these data help identify biologically meaningful targets for chronic pain treatment.

Clinically, even modest reductions in pain can be transformative. On a standard 10-point pain scale, a 25% reduction can shift pain from an 8 to a 6, making it bearable, or from a 5 to a 3, rendering it barely perceptible.

“Our goal is to link these pain experiences to measurable changes in neuronal firing patterns and gene expression,” Akopian said.

Transcriptomics reveals unexpected specialization

One of the most powerful tools driving the study is transcriptomic profiling. Since 2015, Akopian and his team have completed dozens of studies analyzing neurons from the trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia.

“Our work — and that of a parallel NIH consortium known as Precision U19 — has revealed that trigeminal neurons are far more specialized than previously thought,” Akopian said. “Neurons that innervate facial skin are not the same as those that innervate muscles, joints, the tongue or the dura mater, which is involved in headache.”

The team is now about 80% complete with a comprehensive map of neurons that innervate key facial muscles involved in chewing and speech, as well as the temporomandibular joint itself. Each neuron type is distinct in both gene expression and functional properties. Once completed, the map will represent a major advance in understanding the biology of facial pain.

Building shared data resources

In addition to experimental findings, the consortium will contribute transcriptomic and clinical data to NIH repositories. These include patient questionnaires and molecular datasets.

“These centralized, harmonized datasets are essential for high-quality meta-analyses,” Akopian said. “NIH wants to eliminate the bottleneck created by incompatible datasets by ensuring data are validated and accessible to qualified investigators.”

This secure, standardized approach accelerates discovery while protecting patient privacy and data integrity.

Toward non-opioid solutions for chronic pain

The detailed mapping and mechanistic understanding of TMJ pain provides a framework for discovering novel, non-opioid pain therapies. The long-term goal is to develop treatments specifically designed for chronic pain — not just acute pain.

Most existing pain medications temporarily suppress symptoms but do not prevent pain from becoming chronic. Some, such as opioids, can lead to tolerance and dependence, requiring escalating doses and carrying a risk of addiction.

“Our goal is fundamentally different,” Akopian said. “We want to pinpoint that transition from acute to chronic pain. When chronic pain is already present, we want to actively resolve it. This requires targeting the biological mechanisms that sustain chronic pain, not just masking symptoms. A drug that truly prevents or resolves chronic pain would be revolutionary.”