New paper provides plausible biological mechanism for chemical intolerance

Contact: Steven Lee, 210-450-3823, lees22@uthscsa.edu

SAN ANTONIO – A newly published paper provides a long-sought link between environmental exposures and conditions like Gulf War syndrome, breast implant illness, chemical intolerance and possibly even long-haul COVID-19. This discovery represents a major step toward improved diagnosis, treatment and prevention.

The new study by researchers at The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, also known as UT Health San Antonio, as well as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the AIM Center for Personalized Medicine, supports mast cell activation syndrome and mediator release (MCAS) as an underlying mechanism for chemical intolerance.

Mast cells are considered the immune system’s “first responders.” They originate in the bone marrow and migrate to the interface between tissues and the external environment where they then reside. When exposed to “xenobiotics,” foreign substances like chemicals and viruses, they can release thousands of inflammatory molecules called mediators. This response results in allergic-like reactions, some very severe.

These cells can be sensitized by a single acute exposure to xenobiotics such as pesticides or solvents, or by repeated lower-level exposures, such as breathing volatile organic compounds (VOCs) associated with remodeling or new construction. Thereafter, even low levels of those and other unrelated substances can cause the mast cells to release the mediators that can lead to inflammation and illness.

Although mast cells were identified more than a century ago, only in the past 10 years have researchers described MCAS.

“Advancing our understanding of mast cells offers the potential to predict, prevent and treat many exposure-induced illnesses,” said Claudia S. Miller, MD, MS, professor emeritus in the department of family and community medicine at UT Health San Antonio, and lead author of the study. “This understanding opens a new window between medicine and environmental exposures.”

Environmental Sciences Europe, a journal reaching regulatory toxicologists worldwide, published the study Nov. 18, titled, “Mast cell activation may explain many cases of chemical intolerance.” Authors include Dr. Miller; Raymond F. Palmer, PhD, a professor in family and community medicine at UT Health San Antonio; Nicholas A. Ashford, PhD, JD, of MIT; and Tania T. Dempsey, MD, and Lawrence B. Afrin, MD, of the AIM Center in Purchase, New York.

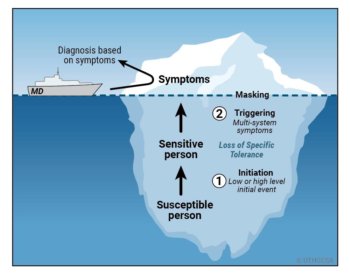

Dr. Miller first identified a two-stage disease process called toxicant-induced loss of tolerance (TILT), from her background as an allergist, immunologist and environmental scientist to explain a new class of environmentally initiated illnesses.

Dr. Miller first identified a two-stage disease process called toxicant-induced loss of tolerance (TILT), from her background as an allergist, immunologist and environmental scientist to explain a new class of environmentally initiated illnesses.

It starts with an acute environmental exposure or a series of lower-level exposures. Subsequently, affected individuals report that exposures to formerly tolerated chemicals, foods and drugs trigger multisystem symptoms.

“The elusive nature of the mast cell and the two-step TILT process have interfered with our understanding of the cause-and-effect relationship between many exposures and complex illnesses,” Dr. Miller said.

But researchers in the new study found a close correlation between patients diagnosed with MCAS and individuals reporting chemical intolerance via a 50-question instrument called the Quick Environmental Exposure and Sensitivity Inventory (QEESI), the international reference standard for diagnosis of chemical intolerance.

As the likelihood of patients having MCAS increased, their likelihood of being chemically intolerant similarly increased, with nearly identical patterns of symptoms and intolerances. The close correspondence between MCAS and TILT patients suggests that environmental exposures disrupt mast cells, and may underlie both of these challenging conditions.

“As primary care physicians, we see patients, sometimes entire families, with mysterious, multisystem symptoms, and ‘allergic-like’ intolerances after moving to a different home, workplace or school,” said Carlos Roberto Jaén, MD, PhD, FAAFP, chair of family and community medicine at UT Health San Antonio. “Often, we are first to hear about symptoms attributed to particular exposures to chemicals, smoke, mold or even an implant.

“With this paper,” he said, “our understanding of the role of environmental exposures in illness just grew.”

Take the BREESI

Here is a three-question initial screening tool for chemical intolerance, called the Brief Environmental Exposure and Sensitivity Inventory (BREESI):

1. Do you feel sick when you are exposed to tobacco smoke, certain fragrances, nail polish/remover, engine exhaust, gasoline, air fresheners, pesticides, paint/thinner, fresh tar/asphalt, cleaning supplies, new carpet or furnishings? By sick, we mean: headache, difficulty thinking, difficulty breathing, weakness, dizziness, upset stomach, etc.

2. Are you unable to tolerate or do you have adverse or allergic reactions to any drugs or medications (such as antibiotics, anesthetics, pain relievers, X-ray contrast dye, vaccines or birth control pills), or to an implant, prosthesis, contraceptive chemical or device, or other medical/surgical/dental material or procedure?

3. Are you unable to tolerate or do you have adverse reactions to any foods such as dairy products, wheat, corn, eggs, caffeine, alcoholic beverages or food additives (e.g., MSG, food dye)?

If “yes” to any of these questions, go to https://TILTresearch.org to find a link to download the QEESI and for more information.

Go here to read a report on a paper published earlier this year by UT Health San Antonio researchers and others that reviewed eight events in which groups of individuals shared the same exposure to chemicals and developed multi-system symptoms and new-onset intolerances. Those individuals included employees at U.S. Environmental Protection Agency headquarters after new carpeting was installed; Gulf War veterans; casino workers exposed to pesticides; pilots and flight attendants exposed to fume events; firefighters responding to the World Trade Center tragedy; surgical implant patients; those exposed to mold at home or in the workplace; and tunnel workers exposed to solvents.

And go here to read a report on a recent study that validates use of the BREESI to initially screen patients for chemical intolerance, and concludes that the condition likely affects one in five people.

Mast cell activation may explain many cases of chemical intolerance

Claudia S. Miller, Raymond F. Palmer, Tania T. Dempsey, Nicholas A. Ashford and Lawrence B. Afrin.

First published: Nov. 18, 2021, Environmental Sciences Europe

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, also referred to as UT Health San Antonio, is one of the country’s leading health sciences universities and is designated as a Hispanic-Serving Institution by the U.S. Department of Education. With missions of teaching, research, patient care and community engagement, its schools of medicine, nursing, dentistry, health professions and graduate biomedical sciences have graduated 39,700 alumni who are leading change, advancing their fields, and renewing hope for patients and their families throughout South Texas and the world. To learn about the many ways “We make lives better®,” visit http://www.uthscsa.edu.

Stay connected with The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio on Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram and YouTube.

To see how we are battling COVID-19, read inspiring stories on Impact