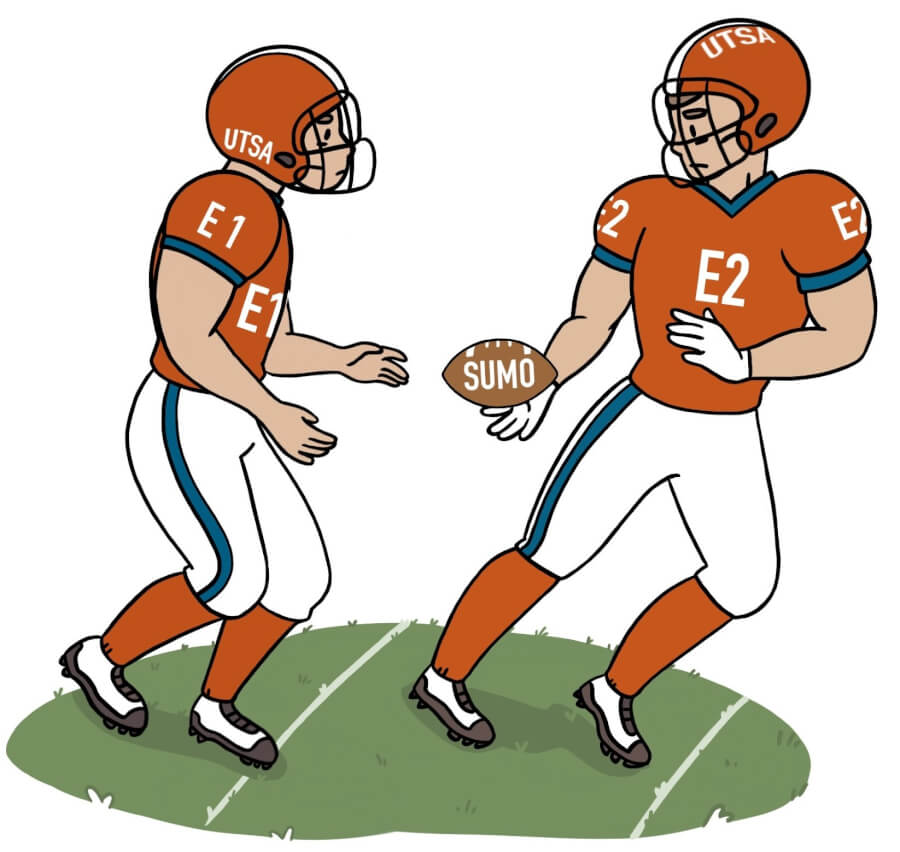

A recent study by scientists at The University of Texas at San Antonio’s Health Science Center used cryo-EM to show how certain enzymes pass SUMO along a pathway, similar to handing off a football during a game.

When a protein is modified inside the cell, it can change how that protein works, either by turning on or shutting off vital functions. One important system that controls these changes is called the small ubiquitin-like modifier, or SUMO, pathway, which affects many actions including DNA repair and stress response.

Scientists at The University of Texas at San Antonio’s Health Science Center have visualized a crucial part of this process for the first time, revealing new molecular details that provide the groundwork for future drug discovery efforts.

Their findings, published Sept. 25, 2025, in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, describe how enzymes in this pathway work together to hand off molecules through a cascade of steps.

The study was led by Shaun Olsen, PhD, professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Structural Biology at the Joe R. and Teresa Lozano Long School of Medicine and co-director of the health science center’s cryo-electron microscopy, or cryo-EM, facility. The lab uses advanced imaging technology that can visualize proteins at near-atomic resolution.

SUMO explained

SUMO is what is known as a post-translational modifier, which means it can alter the functions of proteins after they are made in the cell. It plays an important role in nuclear architecture, DNA damage repair and replication, regulation of transcription and more. Because SUMO is involved in many essential cellular functions that can be disrupted in cancer, it represents a promising target for new therapies.

There are seven ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like modifiers that are all structurally similar to SUMO. Olsen’s team aimed to discover how SUMO recognized and activated its unique pathway and not one of the other six.

The research revealed that the E1 enzyme in the SUMO pathway undergoes a dramatic, nearly 180-degree rotation during the reaction to transfer SUMO to the E2 enzyme. Both shape complementarity and charge compatibility guide the interaction, revealing how E1 and E2 fit together like a key in a lock.

“We know that it does two things — it activates SUMO, and it hands it off to the next enzyme, like a football going downfield. That enzyme passes it on to the next one and it ultimately gets attached to the target protein,” Olsen said.

Previous studies focused on a different surface of the E1 enzyme, but the new structure reveals a distinct conformation that could guide drug development in a novel way.

“Because this structure shows E1 in a new state, it could open up a different way of thinking about drug development,” Olsen said.

Seeing what others could not

Olsen said this new discovery was made possible through the state-of-the-art cryo-EM system at the health science center. Cyro-EM is significantly better suited for large proteins that are conformationally variable and that have some degree of flexibility, Olsen explained.

“We made rapid progress on the project thanks to having the cryo-EM here. Before, people had tried to crystallize these proteins and couldn’t get the whole picture. Cryo-EM let us see it in a new way.”

Launched in 2022, the cryo-EM facility in the Long School of Medicine was co-founded by Olsen, Elizabeth Wasmuth, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Structural Biology and co-director of the cryo-EM facility, and Patrick Sung, DPhil, director of the Greehey Children’s Cancer Research Institute, associate dean for research and professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Structural Biology.

Since its opening, the cryo-EM facility has enabled researchers to study larger and more flexible protein complexes that are difficult or impossible to capture using traditional X-ray crystallography or nuclear magnetic resonance techniques. The facility has helped translate fundamental structural discoveries into biological insights relevant to cancer, DNA repair and other critical areas.

“The cryo-EM facility lets us tackle complex questions about protein function and regulation,” Olsen said. “It’s already pointing us toward new therapeutic targets and strengthening our role as a regional leader in structural biology.”

Nayak, A., Nayak, D., Jia, L. et al. “Cryo-EM structures reveal the molecular mechanism of SUMO E1–E2 thioester transfer.” Nature Structural and Molecular Biology (first published online Sept. 25, 2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-025-01681-8

Read more about the cryo-EM facility:

‘It’s like being able to see a dime on the surface of the moon.’

Assistant professor earns UT System Rising STARs award to advance cryo-EM research

Wasmuth named Howard Hughes Medical Institute Freeman Hrabowski Scholar